Tony Watson.

The Mah Jongg craze which started in the early 1920s in the West, primarily instigated by Joseph Park Babcock (1893-1949) in the US, caused a boom in the production of sets in China, with a consequent depletion of the supply of materials, particularly bone – a situation which prompted a parallel counter-flow of cow-bone from the US to China. The continued boom enabled entrepreneurs to jump on the bandwagon and produce sets in other, sometimes cheaper, materials such as early plastics and to employ processes that were much less labour intensive than the traditional hand-carved, dovetailed tiles required.

The Germans, in particular, were innovators in the use of synthetic plastics; the restrictions imposed by the Allied forces after the defeat in the Great War prohibited trade with China, and so they resorted to the materials they were comfortable with (and masters of), such as plastics. The spin-off from this was cheaper and quicker production methods, standardisation of styles, and consistent quality, attributes which were not ignored by the Western world, or by China for that matter.

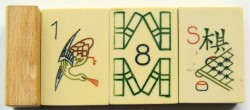

Galalith – from the Greek for milk & stone – was one of the earliest alternative materials. Casein Formaldehyde commonly known as Casein or French Bakelite, was produced by treating casein from skimmed milk (left over from cheese and cream production) with formaldehyde. The resulting material was inert, durable, non-flammable and white – very like bone or ivory. The main advantage was that it could be produced in sheets and impressed with a design prior to formalisation, therefore cutting down on the labour element of carving the tile faces (however, the faces could also be carved). Although cheap, the process was time-consuming, which led to a fall in output when newer moulded plastics came on the scene.

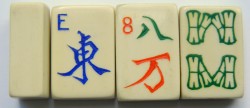

Most of these sets were produced in Germany by the firms Golconda, Marke Pehafra, F.Ad.Richter & Cie, (and others) for the local market (identified by the use of O for East Wind) and probably exported for re-branding by foreign distributors (with the standard ESWN Winds).

Tiles were produced as a solid block, or as a wafer glued onto a wood or fibre base. They are typically hard, sharp-edged, shiny and slightly distorted due to the formalisation process, but can also be pillow-shaped.

Cellulose Acetate, Cellulose Nitrate, Celluloid, Xylonite and French Ivory are very similar allied materials. The latter four are varieties of the same material and have some unfortunate properties, which were not immediately apparent; they can spontaneously combust, are very prone to surface degradation, stickiness and crazing, as well as giving off a distinctive camphor smell.

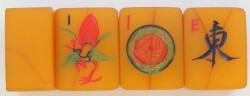

These negative properties led to the mass adoption of Acetate in sheet form from about 1927 and as in powder form from 1930. It can be any colour, either transparent or opaque, and is a very good imitation of amber, horn, tortoiseshell, coral, bone or ivory – materials very familiar to the public at the time.

These negative properties led to the mass adoption of Acetate in sheet form from about 1927 and as in powder form from 1930. It can be any colour, either transparent or opaque, and is a very good imitation of amber, horn, tortoiseshell, coral, bone or ivory – materials very familiar to the public at the time.

French Ivory was patented in 1883 by Jarvis B Edson and improved on by George M Mowbray in 1884, who proposed sandwiching thin layers of slightly different coloured Xylonite in a manner imitating Schreger lines in elephant ivory, (commonly known as cross-hatchings or stacked chevrons).

Excerpt from Xylonite Catalog of 1888:-

Ivorywhite was the first attempt to imitate ivory. Then two shades of this were inter-leaved and pressed together, which gave us our first ‘grained ivory’, hence the word ‘grained’ to distinguish it from plain ivory. The configuration of this ‘grained ivory’ was such that no one could mistake it for the real thing, but it was a beginning, and it says something for the courage of our salesmen to show it as ivory.

Subsequent formulations were a much better simulation of Ivory. Tiles were produced as a solid, a 2-tone solid, wafers of varying thickness on a wooden base, or as a film on a base of wood, card, Paxolin, Ebonite or cement (see Richter’s Anker tiles).

Subsequent formulations were a much better simulation of Ivory. Tiles were produced as a solid, a 2-tone solid, wafers of varying thickness on a wooden base, or as a film on a base of wood, card, Paxolin, Ebonite or cement (see Richter’s Anker tiles).

Other slightly cheaper tiles were plain white with no attempt to imitate ivory. The design was impressed into the surface, the method varied from fairly crude stamping to very finely delineated characters, painted within the stamped lines.

These Acetate tiles are are sharp-edged, shiny, easily dented and commonly lose paint from the design; they are dissolved by acetone.

Bakelite, Catalin and ‘Chinese Bakelite‘ are Formaldehyde-based resins and all appear at first glance to be quite similar, but they have some subtle differences which are still causing debates over identifying tiles today. To add to the confusion, it should also be noted that the BAKELITE trade name was also used by later owners of the Bakelite organisation in connection with other plastics materials, such as polyester and epoxide resins, urea formaldehyde and even polyethylene.

Bakelite (Phenol Formaldehyde) was the first real thermo-setting plastic, but it had limitations in that it required to be set with heat and pressure, meaning hot-moulding, which naturally darkened the material, made it opaque and it could not be produced in white. Bakelite Corporation took the debatable decision in 1928 to solely use this process, leaving the field clear for others to use the casting method. These tiles are brittle with sharp edges, hand-carved designs with well-adhered paint and are not shiny.

Catalin, on the other hand, was a 2-part resin that could be cast, given swirled effects, made transparent or translucent and, more importantly for the Mah Jong trade, white and 2-tone, but sometimes enrobed by casting a contrasting coat around a tile, but leaving the top surface uncoated.

Unfortunately, the early formulations of Catalin were prone to develop internal crazing, which although not a structural weakness was a definite aesthetic negative – Crisloid admitted to this problem in the 1930s.

Unfortunately, the early formulations of Catalin were prone to develop internal crazing, which although not a structural weakness was a definite aesthetic negative – Crisloid admitted to this problem in the 1930s.

Interestingly, this crazing is now seen as an attractive feature and these ‘applejuice’ tiles are very collectable.

In 1933 a patent was taken out by Catalin Corporation for a process of making imitation ivory using a low-temperature process (between 60-80degC), resulting in a more resilient product than the previous brittle formulation. The same patent describes methods of producing resins of varying densities and strengths, by varying the water/glycerine content or curing time – which in turn varies the opacity of the resin – effectively there is no definitive Catalin ‘standard’.

The other problem with Catalin is age-darkening, which turns the original white (or ivory/cream) into that very attractive butterscotch which collectors, particularly in the US, love. The tiles at right are from a set that had never been opened since the 1950’s. There is not much documentary evidence for the original colour of Mah Jong tiles, but white radios made from Catalin are now butterscotch.

Catalin tiles are yellow to dark butterscotch colour, opaque or translucent, have rounded edges and moulded designs, are shiny and often have missing paint. Another diagnostic feature is the lip of resin that appears around the impressed designs – this is very pronounced in some of the American sets.

Catalin tiles are yellow to dark butterscotch colour, opaque or translucent, have rounded edges and moulded designs, are shiny and often have missing paint. Another diagnostic feature is the lip of resin that appears around the impressed designs – this is very pronounced in some of the American sets.

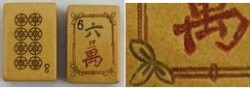

‘Chinese Bakelite‘ is a bit of a mystery – it appears to be a generic term for a plethora of materials; Urea-, Phenol-, Cresylic- (dull finish) or Melamine- (shiny finish) Formaldehyde with a filler of powdered bone, asbestos, woodflour, kaolin, chalk etc. – basically a cheap method of bulking out the expensive resin. It appears that the tiles can be cast or produced in sheets, with impressed or hand-carved designs, and they show the same age-yellowing as Catalin, but often not as pronounced, possibly due to the effects of the filler material. The tiles at the right shows the translucency that many of these tiles have, while the side view of the leftmost tile shows the original white colour after being sanded.

The tiles are typically sharp-edged, usually with sanding marks on the sides. The carving can be naive or very sophisticated, but occasionally the impressed design appears too small for the tile. Often there’s a glued-on back wafer of contrasting colour, but rarely the tiles can be dovetailed onto bamboo.

Urea (Urea Formaldehyde) is used to make high-end sets, primarily from Japan, but imported under various names, e.g. Gibson and Jaques. They are usually of smaller dimensions, but very thick, with deeply moulded designs, very often moulded onto a thin ‘dovetailed’ bamboo or coloured Urea base, emulating the traditional Japanese tiles which have very thick bone or antler faces.The very fine designs were originally carved by a master craftsman and transferred onto a die to stamp the impression during the moulding process.

Urea (Urea Formaldehyde) is used to make high-end sets, primarily from Japan, but imported under various names, e.g. Gibson and Jaques. They are usually of smaller dimensions, but very thick, with deeply moulded designs, very often moulded onto a thin ‘dovetailed’ bamboo or coloured Urea base, emulating the traditional Japanese tiles which have very thick bone or antler faces.The very fine designs were originally carved by a master craftsman and transferred onto a die to stamp the impression during the moulding process.

Paxolin is an allied material to Bakelite – it is a synthetic resin bonded paper, a composite material made of paper impregnated with a plasticized phenol formaldehyde resin, primarily used in the manufacture of printed circuit boards. The brown-orange colour is ideal as a bamboo substitute for backing tiles, but there is no evidence of it being used for that purpose.

Paxolin is an allied material to Bakelite – it is a synthetic resin bonded paper, a composite material made of paper impregnated with a plasticized phenol formaldehyde resin, primarily used in the manufacture of printed circuit boards. The brown-orange colour is ideal as a bamboo substitute for backing tiles, but there is no evidence of it being used for that purpose.

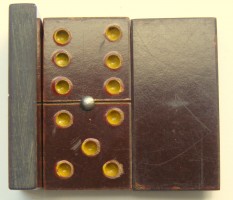

Ebonite is vulcanised rubber with 40-60% of sulphur, producing a very hard, black, rigid material, still in use in industry after 150 years. The material came to prominence in the jewellery arena during Queen Victoria’s long period of mourning, where its jet-like properties were highly valued. An unusual material for Mah Jong tiles (it was commonly used in the UK for dominoes), its aesthetic and material properties lent itself quite naturally to tile production.

Ebonite is vulcanised rubber with 40-60% of sulphur, producing a very hard, black, rigid material, still in use in industry after 150 years. The material came to prominence in the jewellery arena during Queen Victoria’s long period of mourning, where its jet-like properties were highly valued. An unusual material for Mah Jong tiles (it was commonly used in the UK for dominoes), its aesthetic and material properties lent itself quite naturally to tile production.

It was a standard component of the Imperial Company in France (interestingly, the same name as the UK domino manufacturer).

The tiles are hard, resilient but prone to chipping, dull, heavy with a satisfying clunk and usually with a moulded design on the rear, an acetate film melted onto or inlaid into the face and occasionally with gold flecking on the back for the prestige market.

The tiles are hard, resilient but prone to chipping, dull, heavy with a satisfying clunk and usually with a moulded design on the rear, an acetate film melted onto or inlaid into the face and occasionally with gold flecking on the back for the prestige market.

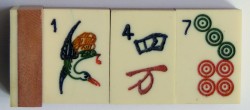

Acrylic/Perspex/Plexiglass/Lucite (Polymethyl Methacrylate) was introduced in the 1930s and found an immediate following in the Mah Jong field. It has many production advantages:- casting, extrusion, fabrication, injection moulding, thermo-forming, some of which were used to make tiles. It is tough, shiny, transparent or opaque, dense and tactile.

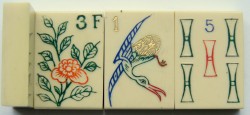

The tiles are very recognisable; the early ones are hand-carved, bright white, generally in 2- or 3-layers, commonly with a clear middle layer and pastel-coloured base, garish design colours, naive design and usually housed in a flat faux-leather zipper case.

The tiles are very recognisable; the early ones are hand-carved, bright white, generally in 2- or 3-layers, commonly with a clear middle layer and pastel-coloured base, garish design colours, naive design and usually housed in a flat faux-leather zipper case.

Melamine (Cyanuramide Formaldehyde) is a very hard, inert, non-transparent and dense plastic that lends itself very well to Mah Jong tile production.

It is a thermo-setting plastic, but can be moulded, produced from post-WWII onward, most notably as the bright 2-tone tableware Melaware.

The tiles feel heavy and cold in the hand with a satisfying ‘clink’ when playing, they can be any colour (including white), often 2-tone, are shiny, but hold paint well.

The tiles feel heavy and cold in the hand with a satisfying ‘clink’ when playing, they can be any colour (including white), often 2-tone, are shiny, but hold paint well.

The German firm Resopal produced a laminate, which was also used for Mah Jong tiles, maybe as a promotional item, but these are rare.

Polystyrene made its appearance in the 1950s and was used in the production of cheap-end Mah Jong sets, as it could be easily injection-moulded, with the added advantage that the design could be incorporated in the mould. However, some very cheap sets have the design ink-stamped onto the faces, whereas others are impressed or etched, giving a much clearer and more durable finish.

Polystyrene made its appearance in the 1950s and was used in the production of cheap-end Mah Jong sets, as it could be easily injection-moulded, with the added advantage that the design could be incorporated in the mould. However, some very cheap sets have the design ink-stamped onto the faces, whereas others are impressed or etched, giving a much clearer and more durable finish.

The tiles are usually hollow and light, but slightly better sets are solid and feel much heavier. They are usually made in 2 halves of different colour and pressed or glued together, are relatively soft and scuff easily; do not feel good in the hand and don’t make a nice sound when shuffling – but they are cheap.

Some tiny, very cheap sets even come still attached to the moulding sprue and have to be self-assembled.

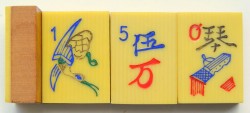

Polyethylene/Polypropylene was first produced in the1950s but didn’t make its mark in the Mah Jong scene until later, then it was typically the large Chinese sets that were made in polyethylene, polypropylene or a mixture of the two, very often 2-tone with very garish colours, but they are hand-carved.

Polyethylene/Polypropylene was first produced in the1950s but didn’t make its mark in the Mah Jong scene until later, then it was typically the large Chinese sets that were made in polyethylene, polypropylene or a mixture of the two, very often 2-tone with very garish colours, but they are hand-carved.

The tiles feel relatively light, waxy/soapy, translucent, with a ‘thud’ rather than a ‘clink’.

Nylon, the polyamide family of plastics, does not seem to have been adopted by Mah Jong manufacturers; whether that is because of price, production techniques or whim, is uncertain.

What is certain is that the modern poly-plastics are very hard for the layman to identify, as many of them have such similar visual and tactile properties, that is is almost impossible to differentiate them without chemical analysis.

ABS (Acrylonitryl, Butadiene & Styrene) resins are a mix of resin and elastomer which give excellent properties and were first produced in the fifties. Their properties are toughness, durability and hardness, which is exactly what is needed in a Mah Jong tile… or a Lego brick.

So if your tiles look and feel like a Lego brick, then ABS is a likely suspect, but as already mentioned, chemical analysis is the final arbiter.

Corian, usually used for high-end kitchen worktops, has been used recently for good quality Mah Jong sets – engraved with CAD process to give high resolution images (except under a lens – not crisp).

Corian, usually used for high-end kitchen worktops, has been used recently for good quality Mah Jong sets – engraved with CAD process to give high resolution images (except under a lens – not crisp).

Natural plastics have been used for millennia, however some – like Gutta Percha, Hide, Sinew, or Rubber – are not suited to Mah Jong tile production, for various reasons, but the following have (possibly) been used.

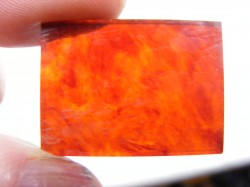

Amber is a natural plastic which has been used for the backing of prestige tiles, and as a response, Chinese Games Co of Montreal produced an Acetate copy (pictured right).

Amber is a natural plastic which has been used for the backing of prestige tiles, and as a response, Chinese Games Co of Montreal produced an Acetate copy (pictured right).

Horn is another natural plastic which has been used for a backing material on high-end sets. It comes in various colours, from light amber to almost black, depending on the source; it is relatively soft, is formed by heat-bending, so will try to revert to its original shape.

Tortoiseshell is actually Turtle shell, primarily from the Hawksbill turtle; it comes in thin translucent sheets and has possibly been used as a backing material on tiles, with a white or silvery reflective surface behind it, but there is no evidence for its use.

Tortoiseshell is actually Turtle shell, primarily from the Hawksbill turtle; it comes in thin translucent sheets and has possibly been used as a backing material on tiles, with a white or silvery reflective surface behind it, but there is no evidence for its use.

Shellac is a resin secreted by the female lac bug (Kerria lacca), on trees in the forests of India and Thailand.

It is processed and sold as dry flakes (pictured at right), which are dissolved in ethyl alcohol to make liquid shellac, used as a sealant on Mah Jong tiles.

There is no record of other use in Mah Jong, probably as the brittle nature did not lend itself to rough treatment – witness the fragile nature of 78rpm records, which were made from ~35% shellac with various fillers, including powdered slate, and coloured with carbon black.

One immediately thinks of wood as the alternative to plastics as a material for Mah Jong tiles, but this is far from the only material used.

Of course, the traditional tiles are made from Bamboo dovetailed onto Cow-bone or rarely Ivory, but these have been covered in detail elsewhere, so we will concentrate on the other materials used.

Bamboo on its own is a cheap alternative to the more expensive Bamboo & Bone, but untreated it is a very difficult material to carve the designs into. Being a grass, not wood, it splinters easily, rendering any carving raggy and indistinct, with consequent bleeding of any painted design.

One solution is to coat the inside (concave) surface of the tile with gesso and carve into that – this produces a much finer result, but is an extra cost in both money and time.

Another method is to plane or sand the inside surface flat, attach a sliver of bamboo enamel (the shiny outer sheath) and carve that – this gives a much more professional finish.

When varnished these tiles can be easily mistaken for plastic.

Some bamboo tiles are dyed black, to simulate ebony, but there is no way they could be mistaken for ebony – wrong weight, texture and appearance.

Wood tiles are very common, produced as a cheap game for learners or children.

The quality of wooden tiles varies enormously; from MDF, particle board and untreated softwood at the cheap end, to expensive, well-finished, lacquered hardwood at the top-end, typically boxwood, but also mahogany/rosewood (however, identification of small, stained samples is difficult).

Although tiles normally have stamped designs, usually mono-colour, (like the delightful German set at right), very often they are faced with paper, celluloid or acetate with printed, etched or impressed designs (or inset, see the red- painted Chad Valley set at right).

Some firms like Parker Bros in the US specialised in a wood sandwich, like thick ply, which came in various shapes, sizes, colours and quality, but generally painted green on the back.

Ebony is a naturally black, very dense African hardwood (Diospyros crassiflora), which was very expensive and is now on the CITES list of endangered species, but it is also a generic term for any black wood.

It is unlikely that Ebony would be used nowadays, but it was not an unusual material in the pre-WWII years – normally not on its own, but faced with Bone, Ivory (as at right), or French Ivory.

More often than not, tiles described as Ebony are a cheaper hardwood dyed black.

Identification is difficult – see website:- http://www.wood-database.com/wood-identification/

Ceramic tiles are very unusual, but as far as can be determined were produced in Germany in the 1920-30s. They are robust, very heavy, and have an under-glazed design as in the set pictured, but the back of the tiles can be a little rough.

Ceramic tiles are very unusual, but as far as can be determined were produced in Germany in the 1920-30s. They are robust, very heavy, and have an under-glazed design as in the set pictured, but the back of the tiles can be a little rough.

There is an example of a Porcelain Mah Jong set in the Mah Jong Museum of Japan.

Jade (Nephrite, Calcium/Magnesium Silicate) or the cheaper, harder version Jadeite (Aluminium/Sodium Silicate), has been used for luxury tiles. It is a semiprecious stone valued much more in the East than the West, and symbolises excellence and purity.

It is a hard, non-crystalline mineral which, depending on the amounts of iron present, varies in colour from clear, white, green, blue, yellow, red or black. Of these, apple green is the most valued, but white is the colour found most in Mah Jong tiles, probably as a result of tile production being concentrated in Shanghai, where the carvers traditionally worked in white Jade.

It is a hard, non-crystalline mineral which, depending on the amounts of iron present, varies in colour from clear, white, green, blue, yellow, red or black. Of these, apple green is the most valued, but white is the colour found most in Mah Jong tiles, probably as a result of tile production being concentrated in Shanghai, where the carvers traditionally worked in white Jade.

Mother of Pearl (commonly abbreviated to MoP) is another material reserved for luxury tiles, reputedly being the ‘essence of the moon’ – one of the Eight Ordinary Symbols.

Mother of Pearl (commonly abbreviated to MoP) is another material reserved for luxury tiles, reputedly being the ‘essence of the moon’ – one of the Eight Ordinary Symbols.

Usually seen as a thin wafer glued onto an ebony or horn base, sometimes it is fixed with a metal or ivory pin. But always very finely carved, as befits the status of the material.

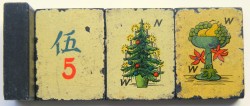

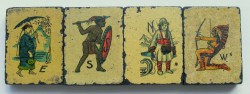

‘Stone‘, or more accurately artificial stone, was the prime material used by the German firm F.Ad. Richter, famous for its Anker building blocks.

Richter used the same material to make Mah Jong tiles, faced with a printed acetate film, then lacquered with shellac which varies in thickness, giving a much darker hue to some tiles. The tiles are an unusual design, featuring ‘races’ for the Wind tiles, and very collectable. The tiles are quite large and heavy, but not thick, however the stone material damages the facing material with use, or even in storage. Very often the tiles were packed before the shellac had dried sufficiently, with consequent adhesion of the acetate film to the reverse of the next layer, which is then ripped off on first usage.

Richter used the same material to make Mah Jong tiles, faced with a printed acetate film, then lacquered with shellac which varies in thickness, giving a much darker hue to some tiles. The tiles are an unusual design, featuring ‘races’ for the Wind tiles, and very collectable. The tiles are quite large and heavy, but not thick, however the stone material damages the facing material with use, or even in storage. Very often the tiles were packed before the shellac had dried sufficiently, with consequent adhesion of the acetate film to the reverse of the next layer, which is then ripped off on first usage.

Cardboard or Compressed Paper was used by many firms for their cheap or entry-level sets. Typically the tiles are thin (3-4mm), but can be up to 10mm thick and are often quite large, for use by children or learners. Normally the design is printed on the top surface, but can be embossed or have a printed acetate film affixed.

Cardboard or Compressed Paper was used by many firms for their cheap or entry-level sets. Typically the tiles are thin (3-4mm), but can be up to 10mm thick and are often quite large, for use by children or learners. Normally the design is printed on the top surface, but can be embossed or have a printed acetate film affixed.

Of differing sizes, the modern first set is from Michael Stansfield, the second set from Chad Valley – both in UK – whereas the third ‘Jeu des Dragons’.set is from a French manufacturer – JTR of Paris (both of the latter are pre-WWII and are showing their age)

The similarity in style of the 2 sets pictured at right tend to suggest that the printed sheets were bought in from a common vendor and applied to the card tiles at the local factory.

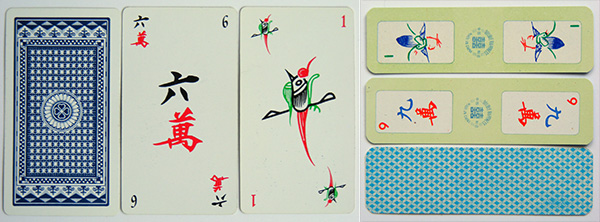

Paper is the ultimate in cheapness, but also portability. The disadvantage of tile sets is the sheer bulk, whereas in playing card form they can be slid into a pocket to play at any time.

Paper is the ultimate in cheapness, but also portability. The disadvantage of tile sets is the sheer bulk, whereas in playing card form they can be slid into a pocket to play at any time.

The downside is they are very vulnerable to damage, wear, dirt, and of course they are easily lost.

Mah Jong cards come in a variety of shapes and quality, from thin pasteboard cards resembling Ma Tiao cards, to the instantly recognisable size of Western cards made of pasteboard, linen, plastic-covered paper or plastic.

Metal has been used for Mah Jong tiles, rarely by manufacturers producing very light hollow tinplate tiles, either with a lithographic print on the face (as on the right, from a set owned by Tress Barnard) or an applied acetate film.

But they were and are also made as a one-off product, either by silversmiths, by prisoners-of-war or home-made as a DIY project.

The metals can range from cheap easily-worked brass and aluminium, to the very expensive silver and gold. Being un-coloured they must have made play very difficult, adding to the complexity of the game.